-

Office of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue U.S. Department of Treasury 1791-1919

Office of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue U.S. Department of Treasury 1791-1919In the Beginning...

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives’ (ATF) law enforcement legacy began in 1791 when the first tax on whiskey was passed under President George Washington and U.S. Department of the Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. Driven by specific legislation, ATF’s legacy evolved through various eras under the U.S. Department of the Treasury, first as part of the Office of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue created by the U.S. Congress in 1792, and later with the Bureau of Internal Revenue, created in 1862. Today’s ATF Special Agents and Industry Operations Investigators are directly descended from the earliest Internal Revenue Collectors, Deputy Collectors, Assessors, Gaugers, Storekeepers and Inspectors who served during this long historical legacy period. The star badge is believed to be the original issue of that era.

William H. Foote, Deputy Collector 1880-1883 -

Prohibition Unit Bureau of Internal Revenue U.S. Department of Treasury 1920-1926

Prohibition Unit Bureau of Internal Revenue U.S. Department of Treasury 1920-192618th Amendment Splits the Country

On January 19, 1919, Congress ratified the 18th Amendment, banning the manufacture, sale and transport of alcoholic beverages. However, there were no provisional funds for anything beyond token enforcement. Because Prohibition banned the commercial production of liquor, the regulatory and tax collecting functions largely disappeared. The jurisdiction was no longer revenue protection.

Eliot Ness (left) & Andrew Volstead (right)Prohibition Agents (a.k.a Dry Agents) Emerge

Andrew Volstead, a leading Republican member of the House of Representatives, authored the National Prohibition Act, also known as the Volstead Act. The Act was passed over President Woodrow Wilson's objections. It affirmed and further specified the provisions of the 18th Amendment, delineated fines and prison terms for violation of the law, empowered the Bureau of Internal Revenue to administer Prohibition, and classified all beverages containing more than ½ of 1 percent alcohol by volume as alcoholic. Plans for the enforcement of the Act were drawn up and responsibility for policing the 18th Amendment was delegated to the Commissioner of Internal Revenue. On January 16, 1920, the country went dry.

Prohibition had little effect on America’s thirst. Underground distilleries and saloons supplied bootlegged liquor to an abundant clientele, while gangsters fought to control illegal alcohol markets. The mayhem prompted the U.S. Department of the Treasury to strengthen its law enforcement capabilities. On August 26, 1926, Agent Eliot Ness was sworn in as a temporary Prohibition Agent with the Prohibition Unit in Chicago.

-

Bureau of Prohibition U.S. Department of Treasury 1927-1930

Bureau of Prohibition U.S. Department of Treasury 1927-1930Crime Fighters Emerge

In 1927, the Prohibition Unit, failing in its fight against organized crime and corruption, was reorganized into a separate and distinct Bureau of the U.S. Department of the Treasury. A strategy was implemented to train and professionalize the force of new agents around the country. At its peak, the Bureau of Prohibition employed 4,300 people. As criminal syndicates gained control over the illegal liquor industry throughout the country, the new mission of the Bureau emerged — crime fighting. The Bureau targeted gangsters to suppress illicit trafficking.

-

Bureau of Prohibition U.S. Department of Justice 1930-1933

Bureau of Prohibition U.S. Department of Justice 1930-1933Transfer to Justice

By 1930, the crime fighting mission began to conflict with the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s philosophy of voluntary compliance with the laws. The crime fighting activities of the Bureau of Prohibition were transferred to the U.S. Department of Justice. The U.S. Department of the Treasury created the Bureau of Industrial Alcohol to carry out its remaining regulatory functions. Eliot Ness and his cadre of “Untouchables” gained fame for their struggle against Al Capone and other bootleggers in Chicago. Agent Ness’ team of specially trained agents damaged the Capone organization’s ability to carry out its illegal activities, and ultimately led to the indictment of Capone on over 5,000 prohibition violations under the Volstead Act on October 17, 1931.

21st Amendment Ends Prohibition

In 1933, when prohibition ended with the passage of the 21st Amendment, the Bureau of Prohibition and its successor, the Alcoholic Beverage Unit, were dismantled. President Franklin Roosevelt issued an executive order consolidating all Federal agencies enforcing and regulating the liquor industry into one entity. The agents rejoined their former colleagues in the U.S. Department of the Treasury. The new entity became the Alcohol Tax Unit (ATU) of the Internal Revenue Service. In September 1933, Agent Ness transferred from Chicago to Cincinnati as a Senior ATU Investigator, and soon after was promoted to Assistant Investigator in Charge of the Cincinnati office.

-

Alcohol Tax Unit Bureau of Internal Revenue U.S. Department of the Treasury 1934-1951

Alcohol Tax Unit Bureau of Internal Revenue U.S. Department of the Treasury 1934-1951Era of Transition

Neither Prohibition’s repeal nor the government’s liquor enforcement resolved the country’s illegal liquor problem. Repeal required the government to re-establish the legal liquor industry. Registered distilleries that had operated legally prior to Prohibition had been dismantled or required extensive repairs. Stocks of ready-for-sale whiskey were small — less than 7 million gallons. However, bootleggers and moonshiners who had established enterprises during Prohibition not only had huge stocks of aged whiskey on hand, but also controlled the necessary resources to meet public demand.

"Revenuers": The New Enforcers

Law enforcement was critical, not only to stamp out illegal alcohol production, but also to enforce alcohol tax collection. The new ATU faced grave problems. Corrupt local authorities could not be reformed overnight, and the public’s tolerance of liquor rackets resulted in lackluster prosecutors, complacent juries and lenient judges.

Crime syndicates continued operating illicit distilleries, but the ATU seized many plants in the first few months after its creation. With growing support from the public, the hard work of the ATU slowly began to pay off. The ATU managed to dismantle large liquor syndicates and the attitude of prosecutors, juries and courts began to change. Schemes to meet the demand for alcohol included counterfeiting Internal Revenue tax stamps, diverting denatured alcohol for beverage purposes, and erecting and operating redistilling plants for alcohol production. Criminals became craftier – but so did agents. When faced with new criminal tactics, agents devised appropriate countermeasures.

Gang Warfare Threatens Public Safety

Gangs battled viciously for control of underground distilleries and distribution networks. Machine guns continued to be the weapon of choice for these criminals. Gangsters killed each other on street corners, in social clubs and in restaurants. The massacres often resulted in the injury or death of innocent bystanders.

The public, once enthralled with glamorous gangsters, became disenchanted with the violence. Congress passed the National Firearms Act of 1934 and the Federal Firearms Act of 1938. These new laws required licensing and taxing of importers, manufacturers and dealers of firearms and ammunition. The ATU assumed the enforcement of the criminal provisions of both acts marking the first enforcement responsibilities for firearms.

In December 1934, Eliot Ness — just 31 years old — arrived at his new post as the Special Agent in Charge* of the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s ATU in the Northern District of Ohio, with 34 Agents under his command.

Ness would serve as the Investigator in Charge* of the Cleveland Office of the ATU until January 1, 1936, when — after fighting organized crime for nearly 10 years — he resigned from his position to become the Director of Public Safety for the City of Cleveland, putting him in charge of the police and fire departments. He successfully headed a campaign to clean up corruption and modernize both public service institutions.

The ATU gradually acquired additional functions such as regulating alcoholic beverages for consumer protection through labeling requirements and production standards, reviewing advertising materials, and policing industry trade practices. In 1951, the Bureau of Internal Revenue reorganized into the Internal Revenue Service. As a result, the ATU absorbed the Miscellaneous Tax Unit, which was responsible for collecting taxes on tobacco, and the regulatory provisions of the National Firearms Act of 1934.

*Position titles changed frequently, but the responsibilities remained the same.

National Firearms Act Stamp

-

Alcohol and Tobacco Tax Division Internal Revenue Service U.S. Department of the Treasury 1952-1967

Alcohol and Tobacco Tax Division Internal Revenue Service U.S. Department of the Treasury 1952-1967Bootleggers, Moonshiners and Violent Crime

In 1952, the Internal Revenue Service consolidated the internal enforcement responsibilities of alcohol and tobacco under one unit, which became known as the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax Division.

Pursuing illegal liquor operations proved to be hazardous work. From 1934 through the 1960s, 17 investigators were killed and hundreds were injured in gunfire, assault by violators, and high-speed automobile chases.

Campaign Against Sugar

Moonshiners posed their own set of challenges. These small, independent distillers operated outside syndicate groups and supplied whiskey primarily to local populations.

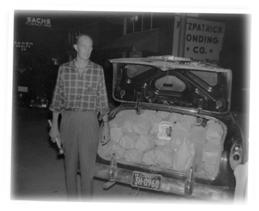

The 1950s “Preventative Raw Materials Program” allowed agents to arrest moonshiners for possession of large quantities of sugar. A parallel campaign urged merchants to deny bulk sugar supplies to suspicious persons.

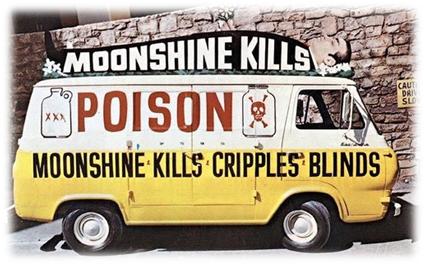

An agent displays evidence from a sugar bust. Moonshine Kills

Moonshine’s poisonous punch is reflected in its nicknames: “white lightning,” “head-buster” and “popskull.” A Georgia agent observed that, “Illicit producers sometimes add manure to make moonshine ferment faster, and we’ve found dead possums, rats and vermin floating in mash vats.” Moonshine-related deaths were so widespread in the 1960s, a government- funded public service announcement campaign was launched.

Treasury vehicles like this promoted public service announcements on the dangers of drinking moonshine.Assassinations and Gun Control

The passage of Title IV of the Omnibus Crime Control Act, and the Gun Control Act (GCA) of 1968, resulted from the assassinations of President John Kennedy, Senator Robert Kennedy and civil rights activist Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The GCA imposed stricter licensing and regulation of the firearms industry, established new categories of firearms offenses and prohibited the sale of firearms and ammunition to felons and certain other prohibited persons.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (Left); Senator Robert F. Kennedy (Center); and President John Kennedy (Right) -

Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms Division Internal Revenue Service U.S. Department of the Treasury 1968-1971

Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms Division Internal Revenue Service U.S. Department of the Treasury 1968-1971Foundation for the Modern ATF

Investigations of firearms and explosives-related crimes and the regulation of those industries became a higher priority within the U.S. Department of the Treasury. This was in large part due to legislation such as the GCA, Title VII of the Omnibus Crime Control Act, Title XI of the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970 and the Safe Streets Act of 1968, which imposed the first Federal jurisdiction over destructive devices. Congress delegated the enforcement of the laws and regulations to the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax Division which, because of its expanded responsibilities in the firearms arena, became known as the Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms Division.

-

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms U.S. Department of the Treasury 1972-2002

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms U.S. Department of the Treasury 1972-2002Birth of an Independent Bureau

Under the leadership of Director Rex Davis, ATF became an independent Bureau on July 1, 1972, and reported directly to the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Enforcement, Tariff and Trade Affairs, and Operations. This reflected important changes within ATF, moving from primarily the investigation of illicit alcohol, to crimes involving firearms, explosives, and arson. Over the next decade, ATF agents applied the ingenuity, experience, and investigative techniques they had used in alcohol investigations to pursue criminals who violated Federal firearms, explosives, arson, and tobacco laws.

ATF Director Rex Davis

-

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives U.S. Department of Justice 2003-Present

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives U.S. Department of Justice 2003-PresentATF Returns to Justice

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks profoundly affected the lives of Americans, and transformed law enforcement across the nation. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 transferred the law enforcement duties and responsibilities of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms within the U.S. Department of the Treasury to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives within the U.S. Department of Justice.